How to Figure out What You Love So You Can Write What You Love

Hey everybody! Thanks so much for being here! My newest post (part of my hopes to put out a post twice monthly) is about figuring out what you love so you can actually write it—hopefully that’s a helpful and welcome reflection as you begin 2022 in earnest!

Side note: I’ve got some cute Valentine’s Day fox art I’m including in this post, but for some reason even though the art looks clean on substack and acceptable on mobile, it looks pixelated on some desktops, so if you view it there and it’s not that cute, I AM SORRY. You can view a cleaner version of the art on my blog.

In a perfect world, writing what you love would be easy. You’d dig deep into your heartsong and out on the page would come, you know, your heartsong—the most passionate, authentic literary expression you could muster.

But we don’t live in that perfect world, and when someone says “write what you love,” my reaction is generally, well duh. As “helpful” and well-meaning as that saying is, it leaves all the heavy legwork to us, the writers, because, “write what you love” still begets the question, “What the heck is that?”

If you are in the camp of illustrious people who somehow know their own heart and everything in it, conscious and subconscious, and already have the answer to what you love, then you have my blessings to go with great speed and write the thing.

But there are many people, myself included, who have to constantly remind themselves what they love, whether due to depression, societal norms, or market pressures. After all, in a world of preexisting stories, in which certain norms are pushed (whether by orthodoxy or capitalism), it becomes difficult to disentangle your stories from the stories that other people want told.

Analyzing what you like isn’t something that comes naturally to everyone. I was raised in a household that told me to actively ignore and repress my intuition, so I empathize with the fact that suddenly needing to have it ring loud and clear can be very difficult. It’s a skill that needs to be consciously and intentionally practiced, much like writing, and it’s a lot of work, but it has many benefits. Not only does pulling away from the dominant narrative and promoting your own voice, social mores, and favorite tropes establish your own novel voice in the world of writing, but it also helps you be a happierwriter, writing the things you love.

In this essay I hope to provide some actionable steps to help you discover (or rediscover) what you, specifically, love in writing.

Behold the cringe-worthy wonder that is your first writings!

“Chelsea, no,” you might say. “Please don’t make me look at my old work. Let us not speak of it!” Do I think a writer’s first writing is an exceptional piece of literature? Not really, but early writing is a good place to look to recall why you started writing in the first place. Pay attention to what younger-you chose to write. Some of the first stories I wrote were Naruto fan fiction, an original dystopia novel that had weapon-summoning, face-paint wearing mimes, and an Eragon rip-off.

In analyzing your early work, pay attention to wha you chose in terms of genre (i.e. European epic fantasy), tropes (“only one bed”), direct inspirations (I.e. fan fiction, plot similarities), or style (I.e. noir).

Action exercises:

What sorts of characters were the protagonists in your first writings? What drew you to them? If you rewrote them today, what would you change?

What sorts of worlds were you obsessed with? What made them stick out in your mind as worth spending time in?

Many young writers mimic other works they admire. Is your work harkening toward another author’s style? Is it similar thematically?

By revisiting the work you did when you first started out, you may be able to re-inspire yourself in the present. Alternatively, if your first writing fills you with despicable self-loathing, then at least you can narrow down that the content of your first writing is not something you love, and continue from there.

Examine your id

Okay, so I’m not using id in the psychological sense that Freud meant, where it’s your most primitive desires of food and shelter—what I mean is that, as a writer, examining your baser desires as a human being in terms of what you value and what you crave can give insight into what you might love to write.

Fo example, let’s say I value community very strongly. If that’s the case, I would probably detest writing a book about an isolationist that spends all of their time alone, and it would also be unlikely for me to write a misanthrope who actively disdains the company of others. If I did write those sorts of characters, whether due to societal pressures or because I thought that’s what the market wanted, I would create obstacles for myself because it would go against my identity. Obviously, writers have things they don’t like in their novels, especially those that cause conflict, but those elements are generally painted as antagonistic.

I once wrote a book called Apostate, about psionics fighting a war in a divided America. At first, the book was about an abused young girl who discovers she’s telekinetic and is able to fight her way into a new life, which I enjoyed because it was about a young woman finding autonomy. But during revisions, the book became less and less about the characters and more and more about the warfare itself between the two sides—the religious Droit and the secular American Commonwealth. I am not a person who values guns or warfare, so when the book became absorbed with those topics (in fight scenes, dialogue, and focus), I became dissatisfied with it. In this way, it’s important to know your values so you don’t accidentally write a book in dissonance with them.

Action exercises:

What values do you like to see in books? Which ones do you abhor?

Which contentious subjects would you like to avoid, if any?

What values and character traits do you think are worth championing in the actions and mindsets of your characters?

Examining the id can also give you a sense of what you crave in a book. Consider “guilty pleasures” in art—things we really enjoy, but aren’t “supposed” to. Even though society disparages our love of these shows, books, etc. there's something about them that satisfies a need.

What you crave in a book usually manifests as wish-fulfillment. Perhaps your main character has super powers, or a really supportive family, or lots of money, or a very impressive skill. These hooks are things that drive reader interest.

Action exercises:

If you could have anything in the world, what would it be? Is there anything you lack in life that you would like to give to your main character?

What’s something you wish you had the power to do? Is there something in life that makes you feel powerless, that you wish you felt stronger against?

Are there evils in your own life (whether moral, or abstract—like loneliness) that you would like to see your protagonist defeat?

Many romance novels fall into some kind of wish fulfillment. Consider the idealized man and, frequently, his idealized wallet family. But other genres also utilize wish fulfillment. Superhero books. Star Wars novels. Espionage. Sword and Sorcery. And more recently, a rush of found-family books, where the protagonists find support.

An example:

I like to say that the biggest fantasy in the Harry Potter books is his friendships, whether it’s his school chums, professors, or his surrogate family with the Weasleys. This, I think, is why people find themselves returning to the Harry Potter books. Harry is chronically surrounded by people who love and support him. The story is an example of someone writing “out” loneliness—Harry starts off neglected and disconnected from anyone relationship-wise and becomes the recipient of a great support network. The books essentially act as a loving, safe space.

So when considering what you love in a book, think about what you lack in your own life—what fantasies you would like to live out, or what stories you would like to see in the world. Those can be good guides to figure out what you might love writing.

One caveat about writing your id: Yes, you want to let your innermost desires drive your writing, but you also want to have a bit of integrity. (A vague thing I don’t know how to tell you to have.) The tl;dr is, essentially, don’t be John Ringo. If you want a few more examples: make sure you’re being tactful when writing the other; give all characters motivations and faults; don’t ascribe to tokenism; if you’re writing about a craft like baking or whatever, bother to research it enough that bakers won’t get mad at you. Etc. etc. Essentially, treat people like real people and practice due diligence.

Think of your favorite works

Go to your fiction happy place and remember the best episodes of your favorite show, the most thrilling moments of your favorite books, the twists that made you scream and shit your pants a little.

For me, I keep coming back to Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Charmed. As a child, I would get up in the morning around dawn and watch an episode or two before school. They were very formative to me, though there are some aspects of them that are super cringe-worthy. As American television series from the late 90s, they feature nearly all-white casts, indie bands in bars, and wayyyy too many halter tops. They also aren’t quite the right flavor of feminist for me (but really, what is? Nothing. The answer is nothing.)

My point is that these shows are stories I got excited about in my youth. I really liked the trio of demon fighting gals in Charmed and I really liked the hero-plus-her-extended-cohort-of-friends ensemble cast of Buffy. I liked that for whatever reason, be it destiny or friendship, it was their duty to fight evil. I liked that evil was easy. Demon bad; human good. (I know there are exceptions canonically, but you know what I mean.) I liked that magic was real, and fighting evil was something the protagonists were extremely capable of doing. I liked the illusion of making a difference. You can’t punchclimate change, but you can sure stake the heck out of a vampire. These are the sorts of elements you can pull from your own favorite works to analyze.

Action exercises:

What are shows that make you feel happy inside? What about them pleases you and makes you keep coming back to them?

Of your favorite shows or books, what elements do they have in common? Elements can be genre, sub-genre, theme, character archetype, plot, etc.

If many of your favorite works do have commonalities, how can you work those elements more effectively into your own stories? How can you learn from where other works went wrong?

Another great exercise is to think of the last book you read that made you happy, or really sparked your interest. This could be a fiction novel, or even nonfiction like history, pop-science, or sociology. Whatever you enjoy, try to capture it—and then put it in your book!

The wonderful world of AO3 tags

If there ever was a codified system of “what you like,” it would be that of the Archive of Our Own (AO3) tag system. If you are unfamiliar with it, AO3 is a database of fanfiction located online. It’s incredibly popular with speculative fiction writers, especially women (and gender nonconforming kids?). It has a user-designed archival system that utilizes tags to divide and group its stories. The tags are based off of things that readers like to see (or avoid) in their stories. Many of them are tropes within fiction, though others include character names and settings.

If you’re not sure what you like, but you do like fanfiction, this is a great place to start looking for what you like, and, even better, it allows you to put a name to the trope that you admire.

So you can get an idea of what I’m talking about, here are some examples of common AO3 tags:

Fluff

Alternate Universe

Angst

Sexual Content

Relationship(s)

Hurt/Comfort

Family

Friendship

Death

Slow Build

Mental Health Issues

Friends to Lovers

Mutual Pining

Child Abuse

Magic

From this list you can get an idea of some things readers might not want to see (I.e. death, child abuse, or sexual content), and things readers might be actively seeking out (I.e. friends-to-lovers, magic, or sexual content). Everyone, readers and writers alike, is different, so the range of tags (and their usages) is quite wide.

If you want to explore the tropes from some of these tags, TVtropes is also a good resource. Their wiki is all about tropes, with real examples from popular books and tv shows.

Action Exercise:

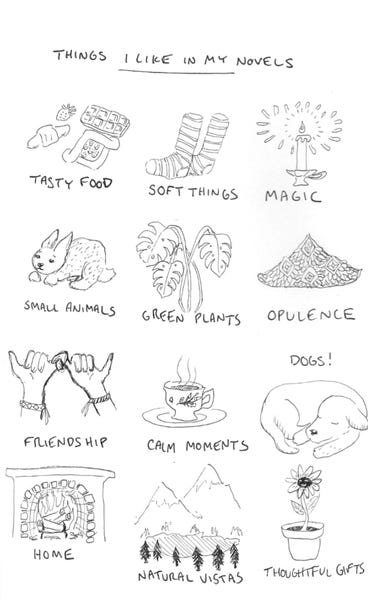

One of the best ideas I’ve heard to spark your inspiration is to make a series of index cards that have some of your favorite tropes on them, so that you can rifle through them at any time to reignite your inspiration on a project. You can have a collection of cards with tropes, favorite archetypes, and elements of works that you’ve enjoyed in the past. Then, whenever you’re down and feeling like you don’t know what kind of thing to write, you can at least remind yourself of the things you enjoy.

A long, long time ago, I did a similar activity, where I drew a collection of things I like to see in writing, so that if I was ever confused about where I stood on things, I would know.

Here is the drawing:

Conclusion

Writing over the long term will always be fraught, emotionally, due to the nature of its competitiveness and the oppressive, incessant nature of rejection. But the process of writing and what you write about has the opportunity to bring you great joy. Hopefully the above tips add a few tools to your toolbox with regards to reminding yourself what you love so that you can continue to write about it—they certainly did for me!

Hello again! Thank you so much for reading my fiddly thoughts on craft! I really appreciate that you looked at my words with your eyes and made images with them in your head! If you think someone in your life could benefit from this post, please feel free to share it with them!

I also welcome new subscriptions at chelseacounsell.substack.com

Best wishes for 2022!