Dollhouses, Throwaways, Parlor Rooms, and Greebles: How to Build Immersive Fantasy Worlds

Recently I was thinking about my time at Viable Paradise, (which I have feelings on, which I will definitely write about at a later point), and I asked myself, what did I learn at Viable Paradise? Obviously, I have friends and connections that I made at Viable Paradise that I probably wouldn’t have without attending the workshop, but what did I learn?

And although a lot of my brain is a blank on that, there is definitely one thing that stands out to me.

You Don’t Have to Describe Everything

One of the instructors brought in a dollhouse. A whole goddamned dollhouse. And put it on a table for us to refer to as they spoke about worldbuilding. (I have since been informed by another graduate that it was a model house, and that may be true—it wasn’t anywhere near as fancy as the one below—but just roll with me on this.)

You don’t have to describe everything in your fantasy world, was the jist of what the instructor said. Imagine the setting of your novel is like a dollhouse. The front facade is detailed with bay windows, shutters, shingles, and balconies. The facade creates the idea of a house in its entirety even though the back is bisected and absent. The facade creates an idea of something more.

If you have ever been in a very large house, you are familiar with the feeling of proceeding inwards and inwards and being kind of bewildered at how far back it goes. How many rooms it has. Dollhouses are not like that. They only have the facade and the front rooms, and then… nothing. Like Naomi Novik’s Scholomance, they open onto the void.

So, at Viable Paradise, I learned that you don’t have to describe everything in a fantasy world. Like a dollhouse, if you describe a “facade” of a fantasy world, your reader will fill in the blanks for the rest of it.

The Power of Throwaway World-building

Supernatural is a long-running, episodic TV show about two monster-hunting brothers, Sam and Dean. The body of the work is so large (fifteen seasons), that there is plenty of time to expand and change the world-building in universe. From their first season to their last, they move from fighting urban legends and ghosts, to taking out demons, angels, and demigods, to being part of a secret society, and even to killing Hitler! Because the body of the work is so large, they have room to do all sorts of crazy crap and have different monsters of the week every episode. In this way, Supernatural has a pretty large leg-up in terms of what world-building it can accomplish just based on the length of the work. But I want to pay special attention to one throwaway line in season thirteen, episode sixteen, Scoobynatural.

For context, Castiel (an angel) has just returned to Sam and Dean’s secret bunker, where he then rattles off a line of hilariously left-field worldbuilding:

The amount I love this line from Castiel is a lot, and for two reasons. One, the actor, Misha Collins, portrays it quite dryly and almost like, tired? Like Castiel is confused but also resigned to his fate of being King Djinn? The other being that it’s a throwaway line of worldbuilding that never comes up again! And I think that’s just so fun and clever. It brings me great joy.

You see, it’s not really important to the plot that the Tree of Life is in Syria, or that it is guarded by djinn, or even that Castiel is now married to their queen. All this is set dressing, played as a joke. If they wanted, the show writers could have had an episode later on where the trio went to Syria and DID meet the djinn queen, but they never did. Regardless, from this one line, they created the space there to step into. Like the dollhouse, the facade is there to open into that “room” of the world. It’s the kind of thing that a fan might remember when writing fanfiction. They might say to themselves, “Hey, Supernatural never explored this Syrian djinn kingdom, but I thought it seemed really cool, so I’m gonna write a whole story in it.” Throwaway lines like this inspire the audience to believe that the world is bigger than what is shown on the screen (or on the page).

The Parlor Room Effect: How Imagineers Create False Depth on Disney Rides

The entire impetus for this post (world building based on false depth), was inspired by a Jenny Nicholson video last October in which she talked about the construction of Disney rides, and how the rides have changed over time. This video was WOWZA for me. Just a big brain moment. Because I instantly connected what she was saying to this idea of the dollhouse or the throwaway line, where the creator (in any media) creates a sense of false depth, and even “re-rideability” in their story by using specific tools to make the world seem larger than it actually is.

In her video (which is behind a paywall on patreon, but this is her Youtube channel), she compares two dark rides from Disney World’s history that stood in the same space in Epcot: Maelstrom, a ride that highlighted Norwegian mythology and culture, which ran from 1988 to 2014, and Frozen Ever After, which opened in the same venue in 2016.

In her video, Jenny Nicholson compares the techniques used to create the two rides, saying:

“Old rides, you had what Imagineers called the parlor room style of ride… You feel like you could ride it multiple times, and look different ways at different times and see and hear different things. It’s like passing through a parlor room full of different conversations happening. [The ride] Pirates of the Caribbean is another good example. It doesn’t have a linear narrative. You’re passing through scenery, with many different characters doing things on a loop, and you can choose where to direct your attention. It makes it feel very rich and lush and re-rideable. But modern Disney, they’ll have set pieces. They’ll have stark and empty rooms, with a spotlight on one really impressive animatronic… You’re going to see it doing the same thing every time you ride. You’re going to see it from the same angle every time, because you’re lined up in the same way with its movements, and there’s nothing else for you to look at in a given room… There’s no point looking in the other direction. It’s just going to be a blank wall… It’s so weird, because Maelstrom was in the same space, but they used things like forced perspective and more creative set dressing… to make it look like you could conceivably be in a larger space with more things to discover.” – Jenny Nicholson

This idea of creating forced perspective on theme park rides got me thinking about set dressing and scenery building within novels. Many writers struggle with the white room effect, where the setting description is neglected so thoroughly that it seems the characters are floating in a white room. (It was definitely a problem for me in my early writing years.) But I also think a “sparse room with one animatronic” might be something to avoid in writing in favor of a lusher parlor room setting. After all, why describe only one facet of the setting when you could describe several?

In theme park rides, the parlor room effect is used to create a sensation of depth that isn’t actually there. Similarly, a linear novel isn’t actually the real world, which you can freely move around in. In order to create the facsimile of depth, your writing can utilize multi-sensory details (never forget smell and taste!) as well as throwaway lines, like the one Supernatural uses, to create a sense of “forced perspective” in the world.

By allowing readers to imagine that things are happening in your world outside of what’s directly on the page, you create a work that has the ability to be reread, and the ability to inspire readers to create fan works.

What the heck are Greebles?

Okay, so at this point I might be just bringing in way too many examples for the average person but HEY WAIT I have one more. (The more the merrier?) In set design, particularly for sci-fi works like Star Wars (1977) and Alien (1979), the designers used greebles (also known as nurnies or widgets) to make their sets look more realized and visually compelling.

Greebles are nonfunctional details that add visual complexity. Using greebles creates the illusion of a more active and interesting surface. Adding nonfuctional details to a surface breaks up the eye’s flow over an object and creates an illusion of scale. (Read more about them here.)

Contrast with images of Star Wars’ Millennium Falcon and Star Destroyer, both models that have been greebled:

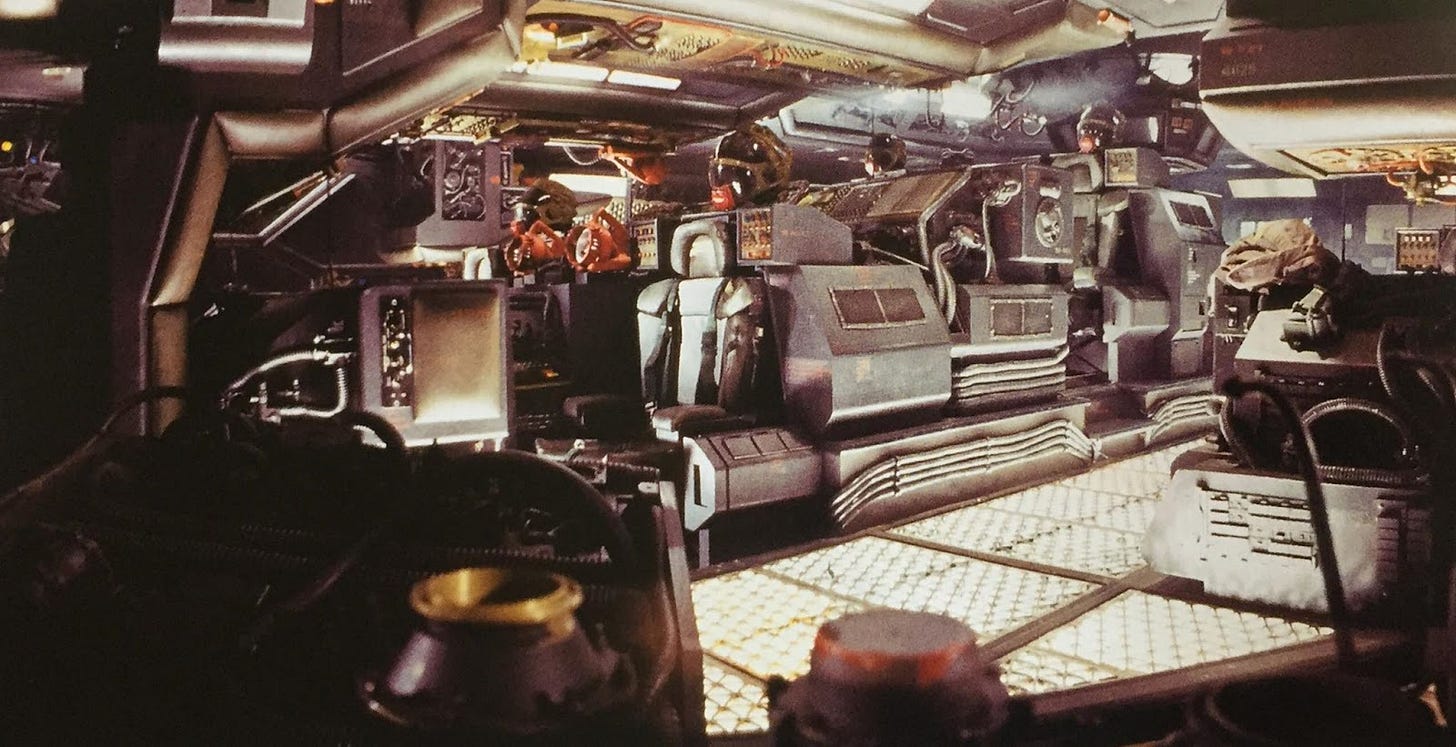

The original word, greeble, seems to come from pieces of kit models used to add visual interest to small models, but on larger models (such as movie sets) designers can even use scrap metal to create visual intrigue:

“In the movie Alien, the interior of the ship Nostromo was thoroughly greebled. Art director Roger Christian said, ‘Let’s have a go at it. So we recruited some dressing prop people, got a hold of several tons of scrap, and went to work on the Nostromo’s bridge… encrusting the set with pipes and wires and switches and tubing… then we painted it military green and began stenciling labels on everything.’ ” – From Greebles, on Wikipedia

Conclusion

Now, you may be thinking, well that’s all interesting information, Chelsea, but how do I actually use any of it to put details into my novel to create a fuller world? And I feel that I could probably write a whole second post outlining that, but here are a few tips:

When writing, imagine yourself as a set designer. What are the most important pieces you need for your sets? How do you decorate your world? What sort of textures, materials, and artistry are added to it?

Think of the space you are trying to create in your reader’s mind. If it’s a spaceship interior, for example, what makes it different than other spaceship interiors? What makes it the same? What kind of “visual activity” or greebles could you add?

In your work, you probably have many characters interacting with each other on the page, but also witnessing events or hearing news off-screen—what might they bring up to each other that would create the illusion of local or global events in your world?

Your POV (point-of-view) character knows certain things, but doesn’t know everything–what do they, specifically, know about the world that would deepen the narrative? For example, if your hero is a pig farmer, they might know a heck of a lot about pigs. How does their pig-rearing knowledge affect their worldview? Alternatively, a weaver might see the world as strands of thread and a beer maker might have a highly potent sense of smell and taste.

What details can you leave out? Sometimes asking yourself what details you don’t need is just as valuable as asking yourself what you do. Your audience does not (usually) want a write-up of your secondary world’s War of Roses. Instead, try brainstorming what your protagonists (and antagonists) actually know about what’s going on and how the conflicts and victories in their world affect them.